Two morbidly similar tragedies hit this past month. Two fathers killed by Staph sepsis. One was the father of three little children at Heschel, our children’s school; the other was the father of Abadi, a soccer teammate and close friend of our son, Kobi.

Staph sepsis is an overwhelming, rapidly progressive bacterial infection that spreads through the blood, resulting in multi-organ failure. Usually, the origin of the infection can be found in the lungs or another organ. In both of these cases, however, the source of the infection remains a mystery.

Both men fought heroically to survive. They had the love and support of their spouses, family and friends, along with the entire arsenal of modern intensive care medicine - fluids, antibiotics, ventilators, pressors, dialysis - everything the ICU had to offer.

But ICU care is mainly supportive. It can hold the line, not win the war. That’s up to the body’s immune system with the help of antibiotics.

Sepsis carries a high mortality rate - a lot depends on age and comorbidities, but not everything. Most people with mild sepsis will recover. For those sick enough to be admitted to the ICU, less than 60% survive. Heartbreakingly, in both of these cases, the defensive line did not hold.

I didn’t know the Heschel dad personally but I knew Andy well. We spent countless hours together over the years, watching our sons practice and play together, with Kobi in goal and Abadi his main defender. Usually, we had our dogs with us - sometimes our wives - and they would play with each other too.

Soccer Moms and Dads are easy to stereotype and parody. I do it myself - especially when we play in Long Island, where the soccer and lacrosse parents tend to put even Giants fans to shame with their full-throated partisanship, at least as compared to we genteel Manhattanites (ah, the narcissism of small differences).

In reality, the parents at MSC, Manhattan Soccer Club, are a diverse bunch from a wide variety of backgrounds and professions. Throwing us together around a common purpose and passion - carpooling to practice, watching the games, traveling to tournaments - can create surprisingly strong bonds.

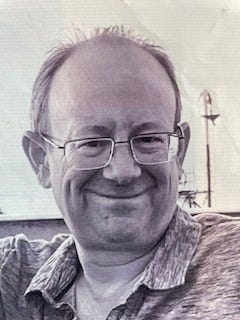

Andy was a theater producer and artistic director of the off-Broadway theater company, Primary Stages. He was thoughtful, intelligent, gentle, and kind. His eyes were magnified by spectacles and he seemed always on the verge of a grin - he had what you might call a smiley resting face.

One felt a certain reserve in Andy that you see in people who are good listeners, more focused on others than they are on themselves. Maybe this came from his work in the theater - actors being a famously high-maintenance crew - where he was respected and beloved.

Even when he cheered for Abadi or the team he held a little back, as if sensitive to the parents and kids on the other side of the field who also deserved to be considered.

Our families live eight blocks from each other in Morningside Heights, so Kobi and Abadi are together a lot - playing video games, sleeping over, or just hanging out. I’m never surprised to see Abadi on the couch or in the kitchen when I come home.

When they were younger, I would walk Abadi home and Andy would meet us halfway, or vice versa with Kobi. Now, as middle schoolers, they roam freely.

I thought I knew Andy pretty well, but at his memorial service, I realized that I didn’t know the half of it. Friends, family, and colleagues from all stages of life eulogised him - relating how he helped them, touched them, mentored them, or guided them.

People told stories made poignant by the occasion but often quite funny. One friend told about visiting Andy in the hospital. Lying in bed surrounded by tubes and wires, Andy looked up at him and asked, “so, how are you doing.”

Can’t really complain….

At one point each of us got a chance to stand up and thank him for something specific. Kobi wanted to thank Andy for always treating him to Shake Shack, but lost his nerve in front of such a large crowd.

Finally, his wife Mary, a wonderful actress, sang Andy a song about love and loss from her recent play, Coal Country. She was accompanied by their friend, the folk legend, Steve Earle. It was almost too much to bear.

One of the hallmarks of sepsis is how quickly the infection spreads. It takes a blood cell about 20 seconds to do a full circuit through the body. That’s how fast the bacteria can travel when it hitches a ride in the bloodstream, from where it can disembark and settle into vital organs at any point along the way.

But sepsis is not the only thing that spreads. So does the impact of a person’s life. It’s easy in medicine to get so wrapped up in the fight against disease that you lose sight of why it all matters.

What we do when we practice medicine has both primary and secondary importance. Primary because the goal is to save lives; secondary because it’s not that we live but how we live - the traces we leave in our wake both before and after death - that truly counts.

Let me explain with a story that took place at a soccer tournament last year. Our team made it to the finals. The game was close and went to penalty kicks. Both sides scored and missed the same number of goals. It came down to the fifth and final penalty kick. We shot and scored. Now it was the other team’s turn and their last chance.

Remember these were just kids. Both the player taking the penalty kick and the goalie were under tremendous pressure. Everyone at the tournament had gathered around to watch. The kicker set up the ball, backed up a few steps, crossed himself, and took his best shot. The ball flew just over the crossbar, missing the goal by about half an inch.

Pandemonium erupted. Everyone on our team ran toward the goal and the boys all jumped up and down in a group hug of delirious celebration.

All except one.

Instead of rushing the goal with everyone else, Abadi walked over to the player who missed the penalty shot. The boy was lying face-down in the grass, sobbing. Abadi bent over, put a hand on the boy’s shoulder, and said something in his ear. Then he went and joined his friends.

I didn’t notice any of this at the time. I was too caught up in the excitement myself. I only saw it on the video afterward. But when I did, I remember saying to myself, that’s Andy!

Of course, it was really Abadi, but it was also Andy. It was indisputable evidence that Andy’s influence had already spread - and continues to ripple out - far beyond the reach of any bacteria or medication.

The ICU is a world in itself, and I know exactly how the dramas that take place there can make it seem like that world is all there is. But while Andy’s death may have been final, it was just one act in a much bigger play.

Maybe that seems obvious but it’s easy to forget. So much depends on where you sit. From the ICU, it no doubt looked like Staph had won the battle; from the memorial, there was no doubt that Andy won the war.

Condolences to all. This graceful and heartfelt post is a reminder of how fragile life can be.

What a beautiful obituary.

Coal Country was an incredibly moving play. Was this the song his wife sang? https://youtu.be/CAEe2ngQCj8