Kong vs. Godzilla

On Clones, Poems, & Dichotomies in Medicine

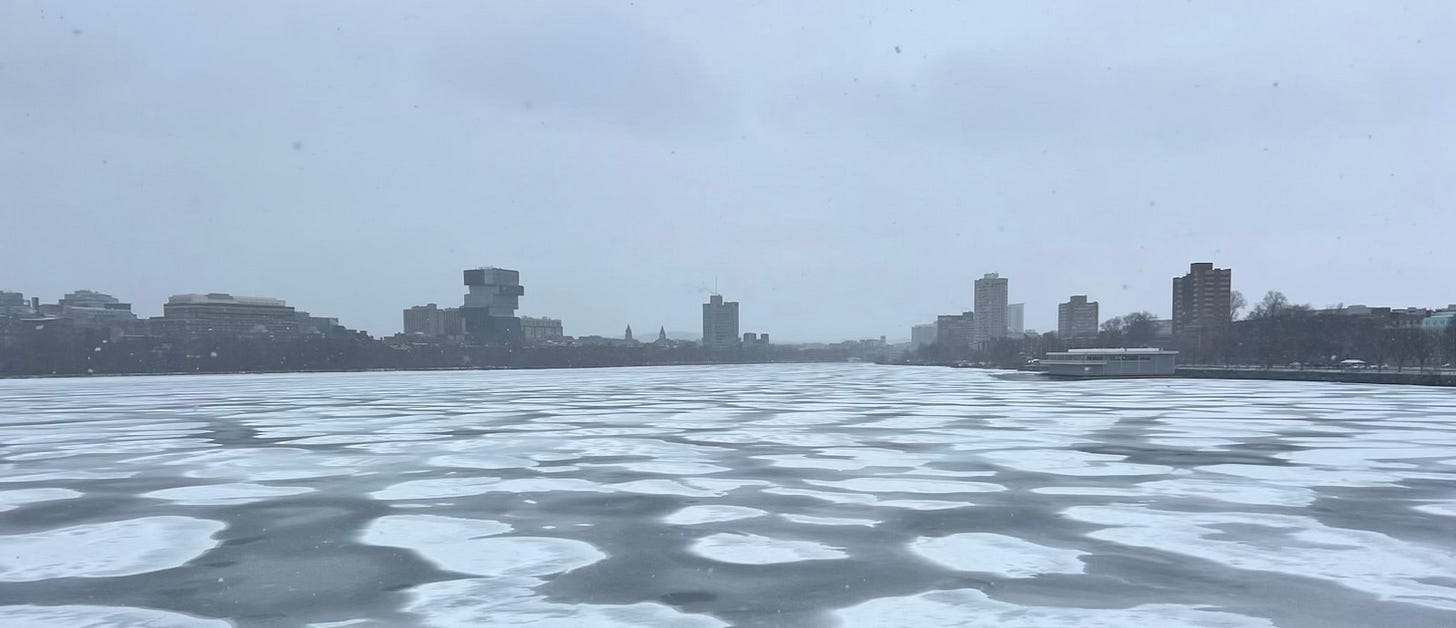

© Photo by Dani Bregman

Much of what we do in medicine is meant to alter or reverse the course of nature. We are born, we get sick, and then we die. Doctors act in the middle to delay the end.

At the same time, we also work in the opposite mode: not to disrupt nature but to align with it. We counsel patients to eat whole foods, exercise regularly, get enough sleep - to attune themselves with natural rhythms.

Rarely do the opposites conflict. It’s not a problem to treat a cold, a broken arm, or even cancer. There is not even the slightest cognitive dissonance. We view illness as our enemy and wellness as our friend, even as they sprout from the same root.

Sometimes, though, the dichotomy rears its head and we find ourselves conflicted. What is our role? It’s not so clear. Should we fight against nature or make peace with it? Sometimes we have to choose.

Take death.

It seems obvious that as far as medicine goes, we are in it to save lives. How many lives have you saved? What doctor wants to answer that with, zero? Obviously, the more the better.

And yet, anyone who has ever worked in an ICU knows better. Knows that there can be a fine line between saving life, and prolonging death in ways that feel unnatural and inhumane. Better to die, we say to ourselves, than to be kept alive like that.

Or take after death.

In a Modern Love essay published in the New York Times last year, Madeline de Figueiredo writes that after losing her 27-year old husband, Eli, in a hiking accident, she was consumed by grief.

Tortured by the fact that there “will never be another conversation, shared laugh, goofy photo, or knowing glance across the Thanksgiving table” she uploads reams of data - photos, emails, voice memos, videos - onto an AI platform.

She is blown away by the result. Every question is followed by a response that Eli could have said, delivered in Eli’s own voice. And each response is entirely novel, in that it had never actually been said by Eli before.

”I miss you,” the AI voice said.

“I miss you, too,” [she] replied through tears.

Meanwhile, back in 1833, Arthur Henry Hallum, the poet Alfred Lord Tennyson’s best friend from college, died of a sudden cerebral hemorrhage. Of course, in those days there was no AI to conjure him up (maybe a Ouija board, but I guess that didn’t work). All Tennyson had was the clash of his memories with the terrible finality of his friend’s death.

What emerged was the poem In Memoriam AHH (1850). Queen Victoria liked it so much that she summoned Tennyson twice to tell him so. She read the poem after the death of her husband, the Prince Consort Albert, and wrote in her journal that she was “soothed & pleased” by the feelings it evoked.

Of course, no one would say, better the loss and the poem than no loss at all. But what if you can’t avoid the loss? Then which is better, the poem or the AI clone? It’s a fair choice. After all, they both seek to achieve the second greatest goal of medicine after saving lives: the relief of pain.

De Figueiredo wrote her article over a year ago - AI 1.0. How long before we will be able to experience not only an audible simulacrum of the dead but a visual, and even tactile one as well? How long before Ouija AI delivers such complete and flawless clones to our senses that we never have to mourn the dead again?

In our dichotomy, this could be seen as disrupting nature.

Tennyson wrote In Memoriam 175 years ago. And yet, as good art will do, it speaks to something universal enough to remain potent today. The poem doesn’t try to change a thing - all it does is describe the world and prove to us that we are not alone.

In our dichotomy, this could be seen as aligning with nature.

Between the poem and the clone, I’ll take the poem. But who am I to say? Here’s a stanza of In Memoriam, where the speaker stalks the empty house of his friend. Read it (out loud) and choose for yourself:

Dark house, by which once more I stand

Here in the long unlovely street,

Doors, where my heart was used to beat

So quickly, waiting for a hand,

A hand that can be clasped no more—

Behold me, for I cannot sleep,

And like a guilty thing I creep

At earliest morning to the door.

He is not here; but far away

The noise of life begins again,

And ghastly through the drizzling rain

On the bald street breaks the blank day.

Interesting title choice! Judging by your last two pieces, I would say it's the winter blues! Excellent reads nevertheless. And that is a damn good poem! No AI can achieve that raw and palpable emotion.

Queen Victoria (not Elizabeth)!